Hi there! I recently read “Designing Data-Intensive Applications”, by Martin Kleppmann, and was fascinated with the concept of building applications around the idea of dataflows. In this blog post, I explain what is the read and write path of an application.

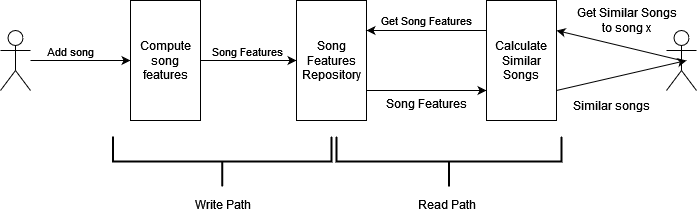

We want to develop a service that, given a user music playlist, generates a list of similar songs to a given song. The service has two flows: the song insertion flow and the similar songs calculator flow. The song insertion flow receives the song, computes the song features, and adds the features to a repository. The similar songs calculator flow receives a song name from the user, calculates similar songs based on the song features and the other songs’ features, and returns a list of similar songs.

Let’s call the song insertion flow the write path, and the similar songs calculator flow the read path of the service. A depiction of both paths can be seen in the following Figure.

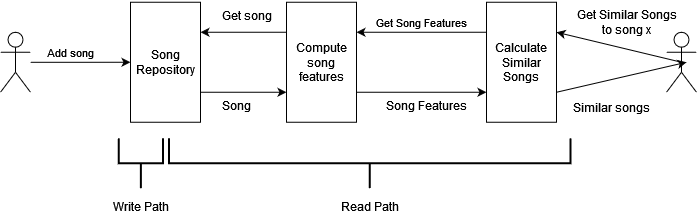

Now imagine that the service is taking too much time to add songs, and that most users add many songs but never calculate any similarity. We can prevent the service to compute the song features by moving that computation from the write path to the read path, as can be seen in the Figure below. The write path is shorter now, at the cost of the computation being done on-demand in the read path.

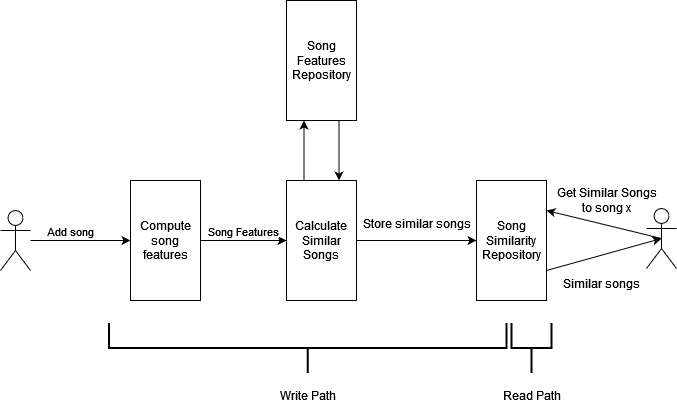

Let’s suppose we have the inverse scenario, that users are complaining because it takes too much time to calculate the song similarities. We can solve that by pre-calculating the similar songs in the write path. In the read path, the user only accesses a repository with the song similarities.

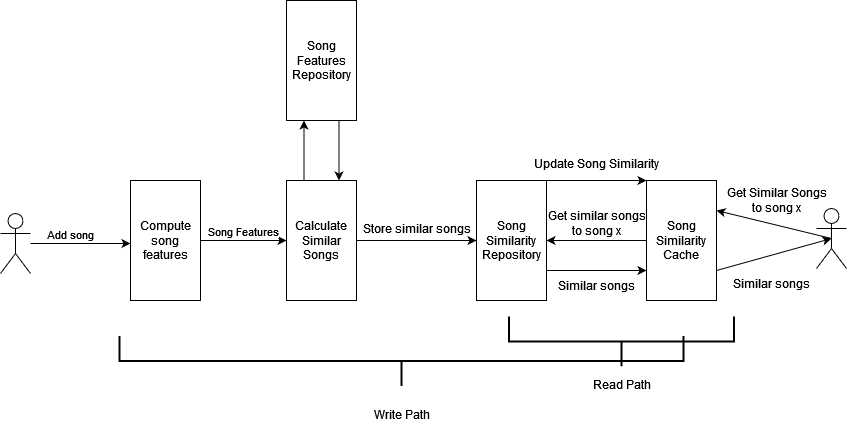

We can go beyond that and add a song similarity cache, that maintains a list of the most similar songs for the most popular songs, speeding up the read path at the cost of a possible cache update on the write path.

The write path is the pre-computed part of the flow and the read path is the part that is only computed by request. In programming terms, the write path is similar to eager evaluation, while the read path is similar to lazy evaluation.

The role of the repository, cache, index or any transformed data view can be seen as the boundary between the read and write path. We can shift the boundary according to our use case needs: if we need fast access to data, we can shorten the read path with additional data views; on the other hand, if we need faster write operations, we can shorten the write path and postpone some data processing to the read path, which will only be done when requested.

When seen like that, in a system when a dataset is derived from another, it shortens the read path and extends the write path, for example:

- When we create a secondary index in a database;

- When we create a full-text search index;

- When we create a machine learning model;

- When we implement a cache.

An example of write and read path shifting is explained in the book “Designing Data-Intensive Applications”. In 2012, Twitter main operations were posting a tweet and view tweets in the timeline. When a tweet was posted, it was stored in a repository with all tweets. When a user accessed its timeline, it was needed to make a query for the people they follow, and then fetch the tweets from them. Due to the heavy load of timeline queries, Twitter systems struggled to keep up. The problem was that the read path - to view the timeline - was doing too much work.

To solve that, Twitter decided on a different approach. Each user would have a cache that had the tweets on its timeline. When someone posted a tweet, Twitter would look up its followers and insert the tweet in each follower cache. The request for the timeline was now much easier - just check its timeline cache.

Did that solve the problem? The downside of this approach was that posting a tweet required a lot of extra work - now the write path was too heavy. Specially for celebrities, which had millions of followers, each tweet would need to be inserted in each users’ timeline cache.

In the end, Twitter moved to a hybrid of both approaches: most users’ tweets were inserted in its followers’ timeline cache, but for users with a large number of followers they weren’t. When a user saw their timeline, Twitter would merge the tweets in the user cache with the tweets from people with a large number of followers.

There are also some architectural examples where shortening the read path can have a tremendous impact. For example, some mobile applications do as much as possible using a local database on the same device without requiring an internet connection and sync with remote servers in the background whenever there is a connection available, practically extending the write path to the user. These design decisions lead to more resilient and efficient applications.

With the popularity of end-to-end stream processing frameworks and tools, such as reactive frameworks, Kotlin Channels, the project Loom for Java or Flux architectures, it is a great time to start rethinking our architectures in terms of dataflow. Instead of treating a database as a passive component, think more about the interplay of state, state changes, and code that processes them. Application code responds to state changes in one place by triggering state changes in another place.

Interesting, right? This is explained thoroughly in the last chapter of the book “Designing Data-Intensive Applications”, by Martin Kleppmann, but I recommend reading the whole book. It is the bible of modern data processing and storage, from the high-level overview to the details of the present databases.

Thanks for reading!