Hi there! This post is the last one in a three-part series about Sentence Embeddings. If you didn’t read part 1 or part 2, you can find them here and here.

In this post, I will explain the State-Of-The-Art (SOTA) approach to create Sentence Embeddings.

Sentence-Bert

Sentence-Bert is currently (April, 2020) the SOTA algorithm to create Sentence Embeddings. It was presented in 2019 by Nils Reimers and Iryna Gurevych [1], and it takes advantage of the BERT model to create even better Sentence Embeddings, taking into account long-term dependencies in the text and the context from many previous timesteps.

To understand the Sentence-BERT architeture, a few concepts must be explained.

Attention mechanism

As said in part 2, the LSTMs have a hidden vector that represents the memory at a current state of the input. However, for long inputs, such as long sentences, a vector does not give all the needed information to predict the next state correctly. The LSTM can make mistakes because, in practice, it only has information from a limited number of steps back, due to the bottleneck of the size of the hidden vector that represents the state.

To solve that, the Attention mechanism ([3], [4]) was introduced in 2014. Instead of a single vector, the model has access to all the previous hidden states before deciding what to predict (a better explanation can be found in [4]). Attention helped with the long-term dependencies problem.

Transformer

Another problem of LSTMs is the time to train. Because the output always depends on the previous input, the training is done sequentially, taking too much time. The Transformer architecture, presented by Google Brain and University of Toronto in 2017 [5], showed how to use the attention mechanism in a neural architecture that could be parallelized, taking less time to train and achieving better results in Machine Translation tasks.

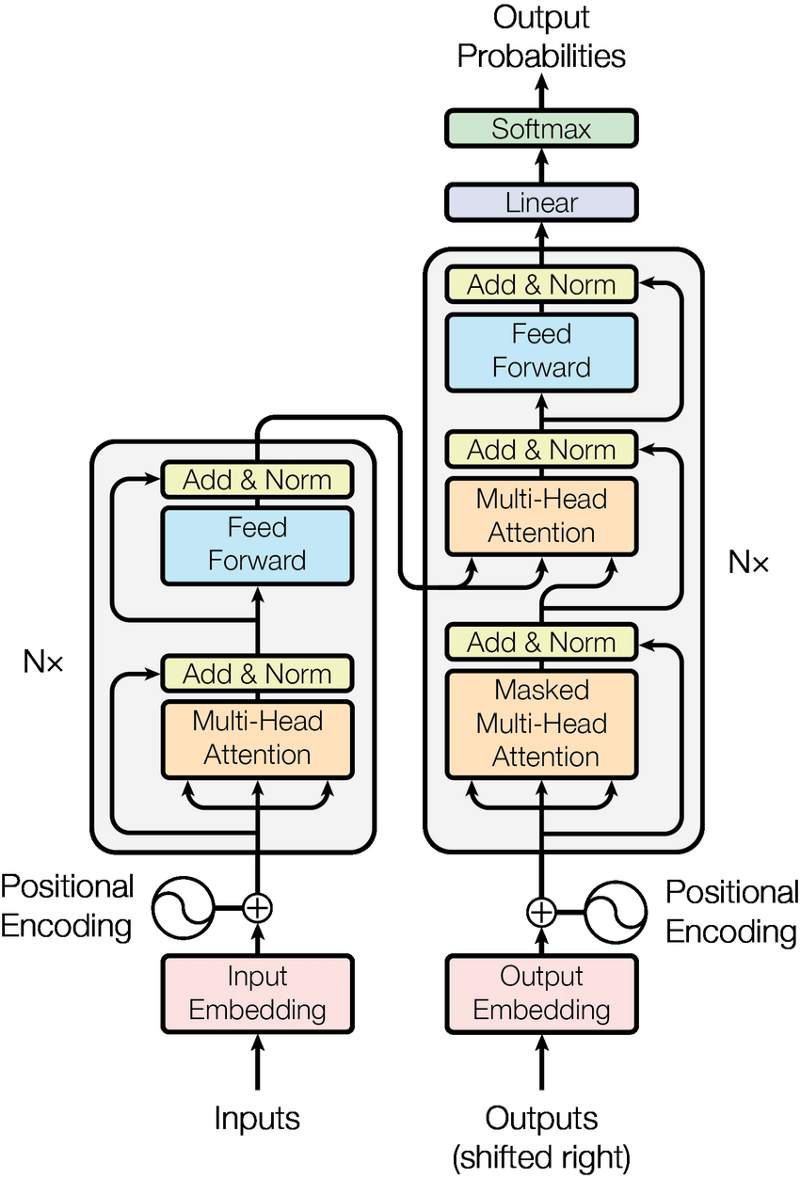

Figure 1 shows the complete architecture of the Transformer. A detailed explanation can be found in [6]. The architecture is composed of two parts: an encoder and a decoder. The encoder encodes the representation of the input, while the decoder tries to output a probability based on the encoder representation and the previous outputs. The encoder and decoder basic building blocks are feed-forward layers and self-attention layers. Self-attention layers look at the entire input and try to pay attention to the most important parts, instead of relying on a single hidden state representation.

The results of the transformer architecture applied to sentence translation resulted in a big improvement over the previous State-Of-The-Art model. The transformer revolutionized the NLP field, because now it was possible to train large datasets in a reasonable time with a model less vulnerable to long-term dependencies problems. However, why should we stick to using just one transformer? What happens if we stack many transformers and train them a little bit differently to obtain better performance?

BERT

BERT was presented in mid-2019 by the Google AI language team [7] and fulfilled the promises of using the Transformers to create a general language understanding model much better than all its predecessors, taking a huge step forward in NLP development. When it was presented, it achieved SOTA results in tasks such as question answering or language inference with minor modifications in its architecture.

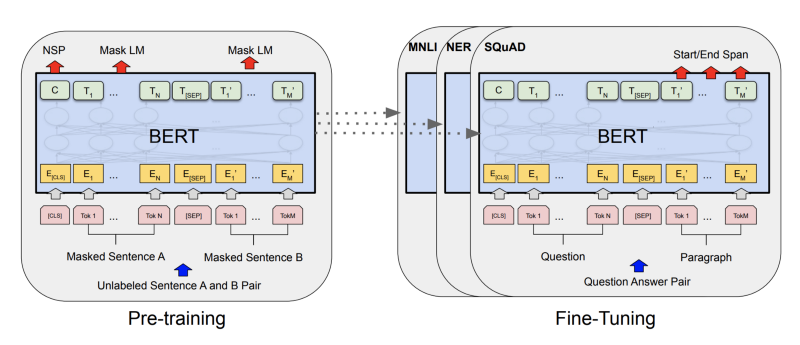

Figure 2 shows the BERT architecture. It is mainly composed of a multi-layer bidirectional Transformer encoder (the large model is composed of 24 layers of Transformer blocks), where the inputs are the Embeddings of each token in the input.

An important aspect of this architecture is the bidirectionality, that enables BERT to learn forward and backward dependencies. That is achieved by pre-training BERT with two different objective tasks:

-

Masked Language Model, also described as Cloze Task, enables BERT to learn bidirectional dependencies. Instead of predicting the next word in a sentence, it masks some percentage of the input tokens at random and predicts those masked tokens. This forces the model to learn not only forward, but also backward dependencies between tokens.

-

Next Sentence Prediction feeds the model two sentences and predicts if the sentences are next to each other. This task forces the model to learn the relationship between two sentences, which is not directly captured by language modeling.

After obtaining the pre-trained model with unsupervised data, the fine-tuning part can be adapted to different NLP tasks, just by changing the input and the output of the model. An interesting conclusion from the paper is that the higher the number of Transformer Layers, the better the results for the downstream tasks.

Sentence-BERT approach

Finally, we reach to Sentence-BERT approach.

To calculate the similarity between two sentences using BERT, it is needed to feed into the network both sentences. Due to BERT complexity, calculating the similarity with 10000 sentences requires approximately 65 hours of computations.

Sentence-BERT is an approach to create semantic meaningful Sentence Embeddings that can be compared with cosine-similarity, maintaining BERT accuracy but reducing the effort for finding the most similar pair from 65 hours to 5 seconds.

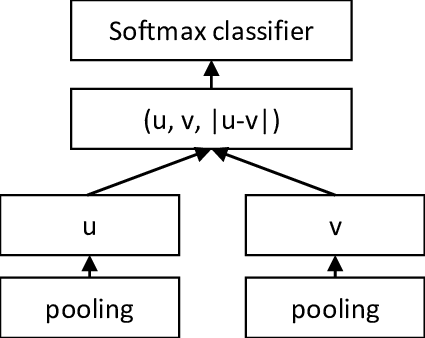

Sentence-BERT architecture is depicted in Figure 3. The training goal (the same used for InferSent) is to classify pairs of sentences according to their similarity: entailment (sentences are related), contradictory (sentences are contradictory) or neutral (sentences are not related). A pair of sentences are fed to BERT, followed by a pooling layer (it can be max pooling, mean pooling or use the CLS token in BERT output), that will generate an embedding for each sentence. Both embeddings are concatenated with their difference and are fed to a 3-way softmax layer. This training schema is often called a Siamese Network [8].

By fine-tuning BERT weights with this architecture, the embeddings generated are suitable for sentence similarity, by sending a sentence through Bert and applying a pooling operation.

Comparing the algorithms

Now that we have seen four algorithms for creating sentence representations (check the previous algorithm here and here), let’s test them and see the results. This Jupyter notebook contains a test with the four approaches.

Given a news dataset, creates representations of the description of the news with the four approaches. Given a query inserted by the user, it will generate a representation of that query and it will compare it with all the news representations. That comparison is done using the Cosine Similarity. The top five most similar news descriptions are printed to the notebook. Let’s analyse some results.

The query was “Democrats win republicans in election.” All approaches produce good results, but it seems that InferSent and Sentence-Bert have better matches. Let’s see another result.

This query is particularly difficult for the first three approaches. Only Sentence-Bert seems to have produced correct results.

You can see more interesting results in the notebook here.

There are other algorithms for producing sentence representations that we tested but they were not explored in this post. If you want to know more I suggest you take a look at Universal Sentence Encoder [9], Skip-thought [10] or FastSent [11].

In summary, there are various algorithms to create sentence representations. Besides its performance, it’s also important to take into account their speed and memory requirements.

Sentence embeddings are an open area of research with big advances in the last few years, and they are in growing demand by industry applications, such as Chat Bots and Search Engines. It is important to keep up the pace with the latest developments in the area of research.

Thanks for sticking by until the last part of this series about Sentence Embeddings!

References

- [1]: Nils Reimers and Iryna Gurevych: “Sentence-BERT: Sentence Embeddings using Siamese BERT-Networks”, 2019; arXiv:1908.10084.

- [2]: Dzmitry Bahdanau, Kyunghyun Cho and Yoshua Bengio: “Neural Machine Translation by Jointly Learning to Align and Translate”, 2014; arXiv:1409.0473.

- [3]: Minh-Thang Luong, Hieu Pham and Christopher D. Manning: “Effective Approaches to Attention-based Neural Machine Translation”, 2015; arXiv:1508.04025.

- [4] - Jay Alammar, Visualizing A Neural Machine Translation Model (Mechanics of Seq2seq Models With Attention).

- [5] - Ashish Vaswani, Noam Shazeer, Niki Parmar, Jakob Uszkoreit, Llion Jones, Aidan N. Gomez andLukasz Kaiser: “Attention Is All You Need”, 2017; arXiv:1706.03762.

- [6] - Jay Alammar, The Illustrated Transformer.

- [7] - Jacob Devlin, Ming-Wei Chang, Kenton Lee and Kristina Toutanova: “BERT: Pre-training of Deep Bidirectional Transformers for Language Understanding”, 2018; arXiv:1810.04805.

- [8] - Jane Bromley, Isabelle Guyon, Yann LeCun, Eduard Sackinger and Roopak Shah: “Signature Verification using a Siamese Time Dealy Neural Network”, 1994.

- [9] - Daniel Cer, Yinfei Yang, Sheng-yi Kong, Nan Hua, Nicole Limtiaco, Rhomni St. John, Noah Constant, Mario Guajardo-Cespedes, Steve Yuan, Chris Tar, Yun-Hsuan Sung, Brian Strope and Rey Kurzweil: “Universal Sentence Encoder”, 2018; arXiv:1803.11175.

- [10] - Ryan Kiros, Yukun Zhu, Ruslan Salakhutdinov, Richard S. Zemel, Antonio Torralba, Raquel Urtasun and Sanja Fidler: “Skip-Thought Vectors”, 2015; arXiv:1506.06726.

- [11] - Felix Hill, Kyunghyun Cho and Anna Korhonen: “Learning Distributed Representations of Sentences from Unlabelled Data”, 2016; arXiv:1602.03483.