Hi there! A lot has been talked about in the last two years of Virtual Threads and how they can revolutionize the Java concurrent programming model and, consequently, increase dramatically the throughput of web applications. But should you use virtual threads in your project? And how they compare with Reactive frameworks or Kotlin Coroutines? Let’s learn more about them and how they work!

Thread per Request model using platform threads

In server applications, concurrent requests are generally handled independently of each other. It makes sense to use a thread per request, because it’s easy to understand, to program and to debug. This means that for these types of server applications, the scalability depends of the number of threads that the server can start and the time they take to process each request.

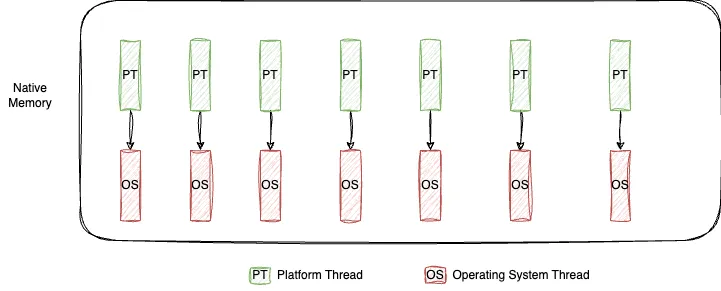

The JVM implements threads as wrappers arount the operative system threads. The problem is that OS threads (also called platform threads) are costly, which means that it’s unfeasible to have millions of them. Even though the hardware resources support much more processing, that is limited by the number of threads that can be created.

Platform threads are costly mainly because of two issues:

- Expensive creation - involves allocating memory for the thread (~ 1 MB), initializing the thread stack and making OS calls to register the thread.

- Expensive context switching - when there is a context switch, the OS has to save the local data and stack for the current thread and load new ones for the new thread. This involves many CPU cycles, as it requires loading and unloading the thread stack, which is not small (~ 1 MB).

Let’s implement asynchronous requests to a blocking method square(int i).

public static int square(int i) {

try {

Thread.sleep(Duration.ofSeconds(1));

} catch (InterruptedException e) {

e.printStackTrace();

}

return i * i;

}

In my machine, using the following code, I am able to create 100 000 platform threads and run the code in 5.39s.

public static void runWithPlatformThreads() throws InterruptedException {

int threadNumber = 100_000;

ExecutorService executorService = Executors.newCachedThreadPool();

IntStream.range(0, threadNumber).forEach(i -> executorService.submit(() -> square(i)));

executorService.shutdown();

executorService.awaitTermination(1, TimeUnit.MINUTES);

}

However, when trying to increase the number of platform threads to 200 000, it throws an OS error.

How can this model be improved to be able to handle more requests concurrently?

Pooled threads

Since the JVM is limited by the number of threads, another possibility is to use a thread sharing system instead of a thread per request. We can create a fixed number of threads and store them in a pool. When needed, a thread is fetched from the pool to start the calculation. After the calculation is done or if it is blocked, the thread is put back into the pool and released.

This model has the benefit of allowing for a much bigger number of concurrent operations with a smaller number of threads. However, it changes the programming style: the programmer needs to explicitly set a callback to complete the processing after the thread is blocked. These callbacks are regularly created as compositions of functions, or pipelines, and each may execute on a different thread.

If you are wondering, that’s how CompletableFuture works and how reactive frameworks are implemented. Let’s take a look at those.

The code below uses CompletableFutures.

public static void runWithCompletableFutures() throws ExecutionException, InterruptedException {

IntStream intStream = IntStream.rangeClosed(0, 100_000);

CompletableFuture.allOf(intStream.mapToObj(num ->

CompletableFuture.supplyAsync(() -> square(num)))

.toArray(CompletableFuture[]::new))

.get();

System.out.println("All computations completed.");

}

This code does a similar calculation using the reactive framework WebFlux.

public static void runWithWebFlux() throws InterruptedException {

CountDownLatch latch = new CountDownLatch(1);

IntStream intStream = IntStream.rangeClosed(0, 100_000);

Flux.fromStream(intStream.boxed())

.flatMap(num -> Mono.fromCallable(() -> square(num))

.subscribeOn(Schedulers.boundedElastic()))

.collectList()

.doOnTerminate(latch::countDown)

.subscribe(results -> System.out.println("All computations completed."));

latch.await();

}

This code does a similar calculation using the reactive framework Mutiny.

public static void runWithMutiny() throws InterruptedException {

CountDownLatch latch = new CountDownLatch(1);

IntStream intStream = IntStream.rangeClosed(0, 100);

Multi.createFrom().items(intStream.boxed())

.onItem().transformToUniAndConcatenate(num -> Uni.createFrom().item(square(num)))

.collect().asList()

.onTermination().invoke(latch::countDown)

.subscribe().with(results -> System.out.println("All computations completed."));

latch.await();

}

The problem with style of programming is that it breaks many of the JVM common patterns: stack traces can be hard to read, debuggers cannot step into the processing and reasoning the overall code is harder. It has a bigger learning curve because it does not seem “regular” Java code.

How can we keep or improve the performance of pooled threads while preserving the thread-per-request model?

What about Kotlin Coroutines?

The Kotlin language, which also runs on the JVM, found a way around the problem of concurrency: to use suspending functions, which is an abstraction similar to a thread, but that still uses thread pools under the hood. The coroutines can suspend their execution and later resume it in another thread. Instead of using the Platform Threads abstraction used by the JVM, the Kotlin language implemented a new framework that can be seen as light-weight threads, because they are very cheap to create and with minimal performance penalties.

Let’s see the same example implemented with Kotlin Coroutines.

fun runWithCoroutines() {

val threadNumber = 100_000;

val latch = CountDownLatch(1)

val scope = CoroutineScope(Dispatchers.Default)

scope.launch {

for (num in 0..threadNumber) {

async { square(num) }.await()

}

println("All computations completed.")

latch.countDown()

}

latch.await()

}

suspend fun square(num: Int): Int {

delay(1000)

return num * num

}

In Coroutines, the user must explicitly suspend the code for the coroutine to block. We must divide our program into two parts: one based on non-blocking IO (suspending functions) and one blocking. This can be achieved using libraries based on Netty, but not every task is easiliy divisible in blocking and non-blocking IO. It’s a challeging task and it requires work and experience do to correctly. While it can be great for advanced users, we lose again the simplicity we want in our programs.

Virtual Threads

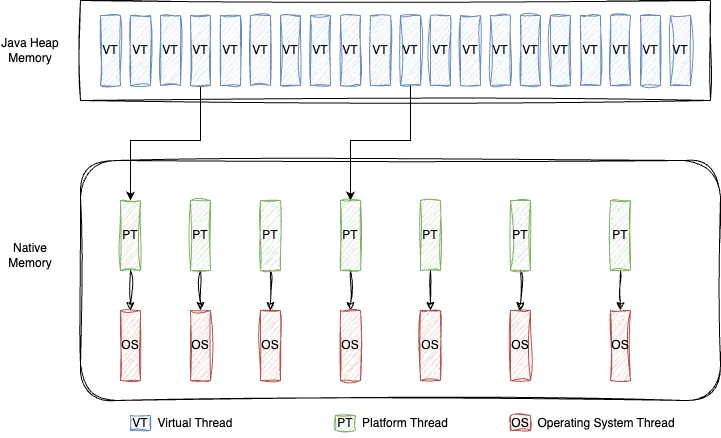

It’s impossible to implement OS threads more eficiently because they are used in different ways by many applications. However, it’s possible to implement an abstraction in the JVM to create as many threads as the user wants, without them being mapped directly to OS threads. That abstraction is called virtual threads.

Virtual threads were first introduced in Java 19 as a Preview API, having its permanent status since Java 21. They are part of a bigger effort of OpenJDK, with Project Loom, to modernize Java concurrency model and improve high-throughput concurrent applications.

One of the biggest improvements of virtual threads is that they only consume an OS thread while they perform calculations on the CPU. The result is that the scalability of the pooled threads is achieved transparently. When a blocking call is done, the virtual thread is suspended until resumed later. Another advantage from the developer point of view is that the virtual threads can be used just like the previous threads, with minimal changes in the code.

The same example implemented with Virtual Threads. If you take a look at the Platform Threads example, you can see that the only change is in the executor service method.

public static void runWithVirtualThreads() throws InterruptedException {

int threadNumber = 100_000;

ExecutorService executorService = Executors.newVirtualThreadPerTaskExecutor();

IntStream.range(0, threadNumber).forEach(i -> executorService.submit(() -> square(i)));

executorService.shutdown();

executorService.awaitTermination(1, TimeUnit.MINUTES);

}

Additionally, this is the faster implementation when compared with all others presented before, just taking 1.41 s to create 100 000 threads and run the code (which contains a blocking call of 1s).

In my machine, if I increase the thread number to 1 million, it takes 1.53s to run all threads, which is still faster than all other alternatives to calculate the same method but just 100 000 times. Impressive!

Why shouldn’t I refactor all my Platform Threads to Virtual Threads then?

The advantage of Virtual Threads over Platform Threads is that it’s possible to achieve higher concurrency, and with that, higher throughput. This makes virtual threads the ideal scenario for short-lived and short call stacks, for example for making an HTTP call or a database query. However, by itself, they do not make the application run faster. For CPU-intensive scenarios, virtual threads bring little to no improvement over platform threads, because since each virtual thread will be bound to a CPU core, they will perform identically to a platform thread.

There is also a specific scenario where virtual threads can lead to worse performance, also known as the pinning issue. This happens when a virtual thread is “stuck” to an OS thread and cannot unmount it, monopolizing the OS thread. That can happen in two scenarions:

- Synchronized methods - If you have a synchronized method inside a Virtual Thread, the thread cannot suspend because it can create deadlocks. To avoid that, Reentrant locks can be used instead of synchronized methods.

- Native method call - When making calls to a native library using JNI, for example.

Should I use virtual threads, a Reactive framework or coroutines?

Virtual threads are ideal for short-lived and short call stacks, for example for making an HTTP call or a database query. If that’s your scenario, they’re probably the right fit. For CPU-bound processes, platform threads continue to be the best option.

It’s not expected that virtual threads totally replace Kotlin coroutines or reactive programming. For more complex projects, Kotlin coroutines offer much more flexibility than any other option, given its structured concurrency approach, channel-based concurrency and actor-based concurrency.

Reactive frameworks are also best fit for projects that involve handling asynchronous data streams and event-driven architectures, with built-in features like backpressure and data stream processing operations, such as stream composition and transformation.

If you want to know more about this topic, there are a few great resources about it:

- https://openjdk.org/jeps/444 - The JEP where Virtual Threads are very thoroughly explained.

- https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=wLJaCXzM6qk - great talk comparing Virtual Threads and Kotlin Coroutines.

- https://blog.rockthejvm.com/ultimate-guide-to-java-virtual-threads/ In-depth explanation about Virtual Threads.

- https://blog.rockthejvm.com/kotlin-coroutines-101/ - In-depth explanation about Coroutines.

Thanks for reading!